Compost | November

Literal and metaphorical compost, wild geese, choices and transformation, rituals to remember, and stories about the dead

I’m definitely composting this month, both literally and metaphorically. At the weekend I spend a satisfying hour or so raking up leaves in the garden and adding them to the compost pile. In my writing life I’ve decided to take half a step back from the big memoir project this month and focus on other, but related strands: online courses, an application for a writing fellowship, a piece for submission. These strands all feel like material to add to the metaphorical compost pile of the big memoir project, material that will enrich and inform my writing when I return to that project next month. Which is all a perhaps overly intellectual way of saying that, having realised I’m not going to complete a first draft of my memoir by the end of the year, it feels good to pause and take a breath, and see what ideas might shimmer into view if I let the dust settle.

So, this month’s Compost post will dive into two themes that are taking up a lot of my headspace at the moment: ancestors and choices. I’ll explore these themes through my usual mix of a bird of the month, tarot card(s) for the month, and some fragments of life writing. I had planned to set myself a writing challenge for November, similar to last year when I challenged myself to write (and publish!) 1000 words a day for 30 days (all 30 of these posts can be found here), but ultimately decided to postpone this as I’m juggling multiple deadlines in both my writing and the day job at the moment. Adding a time-limited writing challenge to the mix felt stressful rather than expansive.

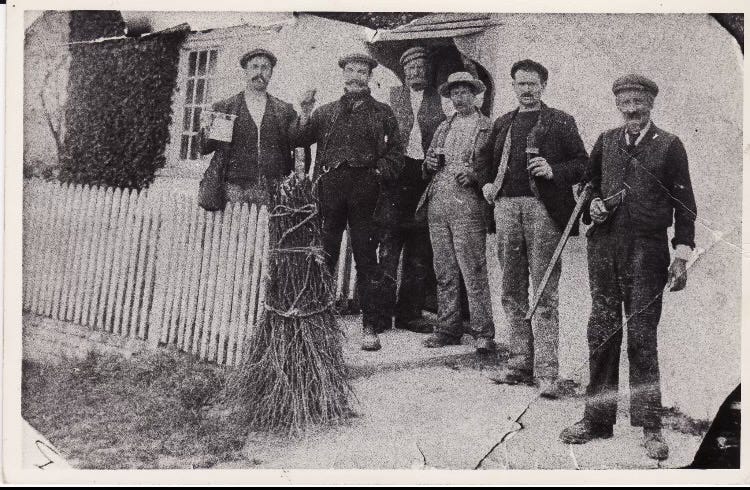

The challenge I’m planning to set myself links into this month’s themes however, and to the Writing from the Archives group programme I’ve just started with Lindsay Johnstone. I want to write a series of short pieces about some of my ancestors: the coal miners and agricultural labourers and coopers and laundry women that make up my family tree, and whose lives I’ve been able to piece together hints of through census records, old photographs and in some cases old newspaper clippings.

Bird of the Month: Greylag Goose

Anser anser, Gwydd Lwyd, Gwydd Wyllt

Some disappointingly literal etymology this month: Anser means ‘goose’ in Latin, and Gwydd Lwyd similarly translates to ‘grey goose’. I’ve included the alternative Welsh name for this bird, Gwydd Wyllt, because it translates to ‘wild goose’ and I want to include a quote from Mary Oliver (yes, that poem - but not the part you’ll perhaps be most familiar with). Greylag geese are a mottled grey-white, with a bright orange beak and bright pink legs. They’re large, probably a similar length and weight to an average newborn baby. They are the ancestor of the domestic goose and, while most of the flocks who breed in the UK migrate south to southern Europe and North Africa for the winter, there are also feral flocks who remain her year round.

I chose a goose for this month’s bird because every autumn they pass over our house in the mornings and evenings, presumably following a familiar migration route south for the winter. If I’m awake early enough I can hear them flying above me as I lie in bed, the creak of their wings and their low calls to each other. It is a delight of the season, but I’ve got the timing slightly wrong and this year the geese seem to have completed their journeys south in October. There’s been no sign of them since November started.

Another reason I chose a goose is because as we move towards and into and through the winter I look to the skies, seeking as much light and colour as I can while the land around me becomes increasingly grey and brown. Traditionally, the Air element is associated with Spring, but I always associate it with Winter: the cold clarity of the air in winter, everything stripped back to its essence. Other things I look to the sky for this month: the final fiery glory of the autumn leaves (the beech trees in particular are a riot of colour at the moment), fireworks for Bonfire Night, and of course the stars. I’m watching out for the return of the constellation Orion, which always signals the arrival of winter.

Similarly, the geese migrating south is a symbol of the changing seasons. There’s something about the sense of movement, their steady wingbeats taking them from this place to another, that I need at this time of the year. They’re leaving, escaping from the cold, dark months that we’re about to enter, but I know that they will return in the spring. That promise of return is so important: we need to know that the Spring will return in order to face the Winter.

Meanwhile the wild geese, high in the clean blue air,

are heading home again.

Whoever you are, no matter how lonely,

the world offers itself to your imagination,

calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting—

over and over announcing your place

in the family of things.

Wild Geese (Mary Oliver)

Choices and Transformation

I’ve picked two tarot cards for this month, perhaps the two cards that people are most likely to take at face value but which also offer deeper, more symbolic interpretations: the Lovers and Death.

Maybe the Lovers represents a new love interest arriving in your life, or predicts that you’ll soon marry, but it is also about choices. Choosing Love. Choosing between two potential lovers, as the Rider-Waite illustration suggests. Choosing to follow one path rather than another. The Lovers card is a reminder that there is always another side to the story, another option, a different decision that we could make. It asks us to follow our heart when we make that choice, to listen to our intuition as well as our rational mind.

As you can see above, the Lovers are represented by two geese in flight in the Wild Unknown Tarot. There’s that sense of movement again, and a hint of how expansive having to make a choice can sometimes be. The geese are heading into the unknown, steering their own course through the skies, so the Lovers card might be a reminder that we can choose to do the same.

The Death card, of course, isn’t necessarily about literal death. It’s unlikely to be a message from the Universe that you or someone close to you is about to die. Instead, Death represents the inevitability of change and transformation. Nothing stays the same. The seasons turn from summer to winter and back again. I am not the same person today as I was ten years ago, or even five years ago. My children keep getting bigger and sometimes I wish I could freeze time for a little. Time passes and we have no choice about the matter. But we can choose how we approach and respond to change, to honour and mark moments of transformation. Rituals are one important way that humans do this. Think of christenings, weddings, funerals - or graduation ceremonies, birthday parties, leaving drinks.

Late October into early November offers a clutch of rituals that I associate with remembering the dead. There’s Halloween, about which in its current commercialised gleeful horror form I am intensely Scrooge-like, while remaining drawn to the older rituals associated with it: soul cakes and dumb suppers laid out for your dead. Then there’s Bonfire Night, which I love for its flames and fireworks lighting up the darkness, but has its roots in a failed terrorist plot and a celebration of the brutally violent way in which the plotters were executed. Finally, Remembrance Day, which falls on my birthday and which arguably is the root of my fascination with memory, the stories we choose to remember and those we don’t. As a child it meant sitting in assembly attempting to think solemn thoughts about the fallen soldiers while internally vibrating with glee and excitement about the birthday presents waiting for me when I got home from school.

Stories about the Dead

I’m itching to dive into exploring and writing about the lives of my ancestors. I’ll be looking into my mum’s side of the family tree for the memoir project I’m currently working on, but I keep being distracted by stories from my dad’s side so I thought I’d share a snapshot of the life of one of my paternal ancestors to round off this post, with a focus on the detective like process of piecing a life lived 150 years ago back together from archival fragments, and the many potential stories you can start to weave from these.

My great-great-grandmother Letitia is known as Letty in the family stories. The bare facts of her life, gleaned from census records and the register of births, marriages and deaths, reads like the plot of a Thomas Hardy novel. She was born in 1845 in Barham, a village in south east Kent. Her father was an agricultural labourer and her mother died before she was 5. Letitia married a man called George in Faversham in autumn 1867, when she was about 22 years old.

By the 1871 census, George is dead and Letitia is living in Faversham Workhouse with her 2 year old son Henry and 3 month old daughter Charlotte. Jump forward 10 years to the 1881 census and life seems to have improved for Letitia: she’s now married to a man called John, a shepherd, twenty years her senior and they’re living near Dover with their 5 children. The eldest, Henry, is Letitia’s son from her first marriage but he’s taken John’s surname. Charlotte is missing from the census record, presumed dead. John and Letitia’s eldest child is my great-grandfather, William, then aged 8. By 1883, Letitia is dead before her 40th birthday.

So far, I’ve given you a pretty dry summary of a not uncommon life story for a female member of the rural working class in the second half of the nineteenth century. But look a little closer and the plot thickens, threads of potential stories suggesting themselves. Letitia and John were never legally married, making my great-grandfather William and his three younger siblings illegitimate. And the reason they never married is because John already had a wife. In the 1871 census John is living in Northamptonshire with his wife Sarah and their five children, aged between 18 and 2 years old. Very soon after that, John seems to have abandoned Sarah and their children for reasons unknown and relocated to Kent, because in 1873 his first child with Letitia is born: my great-grandfather William.

The hint of scandal is enticing, and I wish I could know if my gran, William’s daughter, was aware of her father’s murky origins. I suspect it was a family secret, kept hidden because of the social stigma of illegitimacy. I imagine that John and Letitia moved from Faversham, on the north coast of Kent, to Dover in the south-east of the county, to help hush things up. When they arrived in Dover as newcomers, they could present themselves as already married.

I want to know whether John really abandoned his first wife Sarah and their five children, and if he did, what the reasons were. I wonder if it could perhaps have been a mutually agreed separation, a sort of informal, common law divorce in an era when legal divorce required an expensive court case and could only be granted on the grounds of adultery, cruelty or desertion. I am aware that I may be grasping at straws here in an attempt to prove that my great-great-grandfather was not a cad and a bounder! Then I want to know how John and Letitia ended up together. There’s a potential plot of a romance novel there, with the beautiful young widow and a kind-hearted older man who rescues her from destitution and the workhouse, offering the stability and respectability of marriage and a steady income from his job as a shepherd. It’s easy to spin a story where they fall in love, evidenced by the four children they had together in the decade before Letitia’s death.

This is what keeps drawing me back to researching my family tree: there are so many potential stories hidden there, so many possible narratives I can spin from the few bare facts that are often all I can find out about my ancestors, and always the belief that if I keep digging I might find another fragment of information that will reveal which is the ‘true’ story.

Postscript

Another story from my dad’s side of the family that I’m itching to tell is that of my great-great-great uncle Thomas Wells, the first man to be executed ‘in private’ after they banned public hangings. I briefly mentioned him in my last post. He worked at Dover Priory railway station and was convicted of the murder of the station master in August 1868, being executed by hanging just 12 days after the crime. He was 18 years old. It seems clear that he was guilty of murder (he shot the station master in the head with a gun he had brought to work with him to scare off birds from the railway yard) but there’s a big divide between the way he’s portrayed in newspaper reports from that time and the version of him that has come down to me in family stories. I will definitely write more about Thomas, but I feel like there’s more archival research I need to do before I can do his story justice.

The metaphor of composting for the creative process is spot on. Stepping back from a big project to let other experieces and ideas enrichit makes so much sense. Sometimes what feels like procrastination is actualy necessary incubation time for better work to emerge.

Wow, your family history is fascinating Ellen and I can understand the writerly urge to dive into it all and create stories from it. Looking forward to reading more about your discoveries and the writing they inspire!