Compost | April

This month’s instalment is brought to you by my chaotic brain, the wrong branch of the family tree, cave dwellers, tree knowers, and the number 9.

It’s been a slow month so far on the memoir writing front, and a little voice inside me is panicking that the writing spark has left me, that the well of ideas inside me has run dry and I will have to come clean as a fraud sooner or later, a wannabe writer who might be able to talk the talk but has failed to walk the walk. I’m trying not to listen to it, and to trust the process. There’s been a lot going on this month (and it’s only the 13th). I was solo parenting for a week while my husband was away and took two days of that week off work with the intention of spending those days basking in some much needed time to myself and writing all the words. In reality, I got very little writing done and have been gently berating myself over it ever since. I think it was partly the shock of suddenly having an uninterrupted 6 hours to myself to write, when I’m used to snatching maybe an hour to write each day, often in disjointed fragments of 5 minutes here, 10 minutes there.

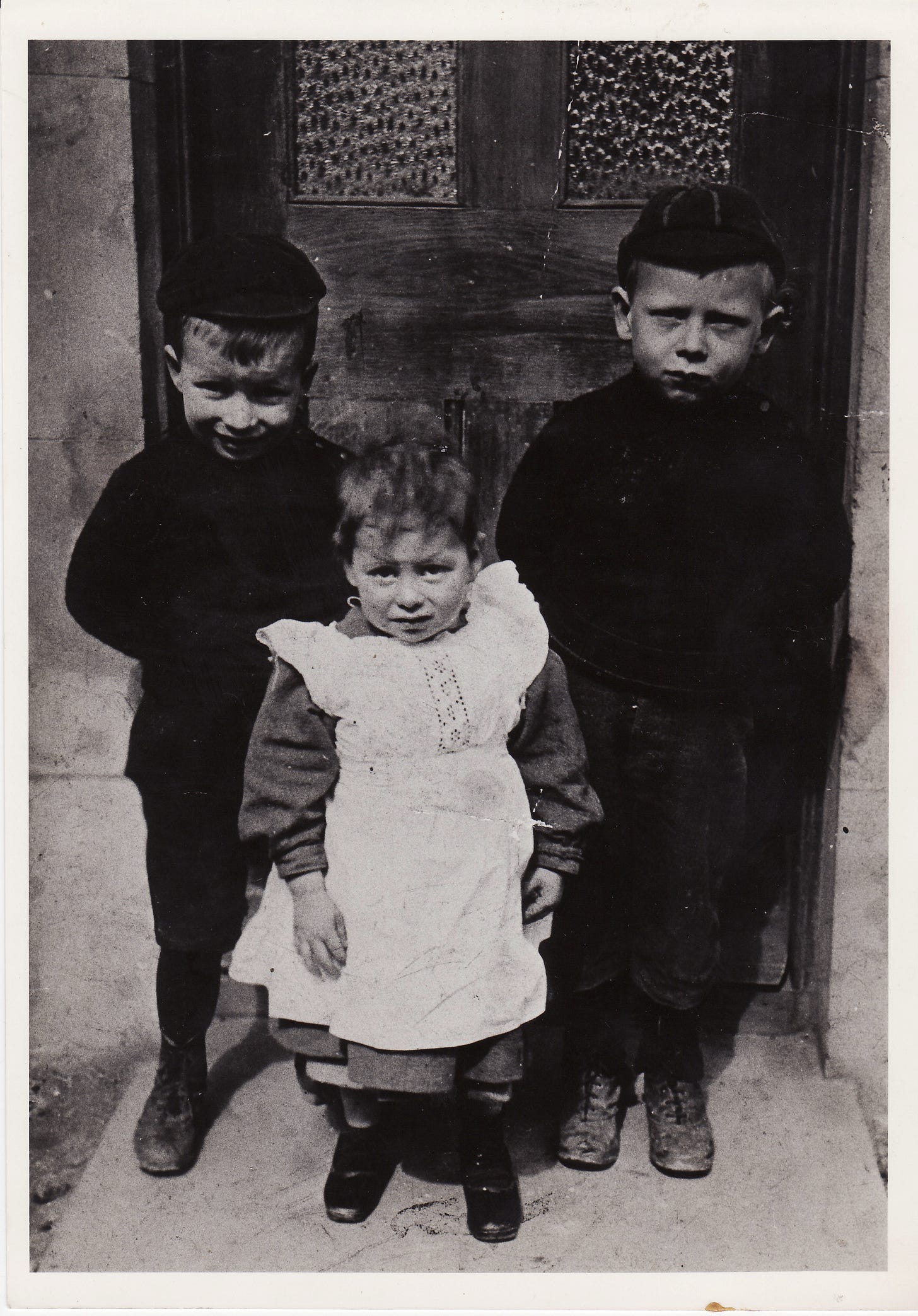

The other topic that’s been taking up my time and attention so far this month is a detour into the opposite branch of my family tree to the one I’m supposed to be writing about. I rediscovered and promptly became obsessed with this old photograph of my paternal grandfather and two of his siblings:

I wrote about it a little on Notes last week. The photograph must have been taken around 1910 and I desperately want to know the story behind how it came to be and who was holding the camera - because I’m certain that no one in their family would have owned one at that point. It looks like it was taken outside rather than in a photographer’s studio, possibly on the front door step of the house they were living in. I’m imagining some kind of travelling photographer, going door to door and asking if the residents would like a portrait taking. It’s posed but not staged (the two boys’ boots are dirty). My grandfather Alf (the boy on the left) has understood the assignment and is smiling, but his older brother Fred looks deeply suspicious of the camera or whoever was standing behind it, and their little sister Florence - who can’t be more than 2 years old - clearly has no idea what’s going on.

This is the oldest family photo we have. I feel very lucky to have this glimpse of my grandfather and his siblings as children over a century ago. It’s a different world, but only two generations removed from my own.

has said that she was taught to look back 5 generations when taking a case history in response to a photograph and story shared of her great-grandmother, and that seems very wise to me. Five generations is how far I’ve been able to trace my family history back, to my grandparents’ grandparents. It’s fascinating to pull together everything I know about the lives of those four generations above me. For many of them it’s just the bare facts of birth, marriage and death, maybe with the addresses of some of the places they lived gleaned from the census. For some, there are scraps of stories to go with these facts, or educated guesses made by putting these family histories into the wider social, cultural and political context.For an even smaller number of individuals, we have photographic evidence of their lives. Starting with my grandad Alf and his siblings on their front door step in 1910, then a trickle of snapshots from the 20s, 30s and 40s: Alf and his bride on their wedding day, my maternal grandmother posing in a bikini on a sand dune, my maternal grandfather walking down a street in Liverpool with his friends. From the 1950s onwards it becomes a steady flow - almost a flood of photos from my mum’s childhood (her father must have been a keen photographer). I love the way that old family photographs can make your ancestors - people you’ve never met, who may have died long before you were born - real and human. It’s easy to find out the hard facts of their lives: my great-aunt Florence, the little girl in the image above, died from meningitis when she was 10 years old, my paternal grandmother’s father died in a warehouse fire when she was pregnant with my dad. Old photographs give you a glimpse into their everyday happinesses and personalities. The mundane memories as well as the traumas.

Bird of the Month: Wren

Troglodytes troglodytes, Dryw

I rarely if ever saw a wren before moving to the house I live in now: a 70s build at the end of a cul-de-sac on the edge of a village, its garden backing on to what is essentially a small patch of woodland. Now, they’re one of the birds I see most regularly in the garden, and certainly one of the loudest. Last year, I kept a list of every type of bird I saw that year, in some cases with the date I spotted them (the first swallow was 6 April 2024). In 2025, I’m trying to learn to recognise birds by their calls using the Merlin bird identification app. It’s been fascinating - not least beacuse it’s made me realise quite how loud wrens are.

This tiny brown ball of feathers, maybe 9 cm long and weighing about the same as an AAA battery, is LOUD, much louder than you would assume based on its size. Like all birds, wrens’ vocal cords (syrinx) are located at the bottom of their wind pipes, much closer to the lungs than our mammalian larynx. The syrinx has two chambers and some birds (including the wren) can alter the shape of each chamber independently, by tightening or relaxing the muscles in their throats, to sing two different notes simultaneously. The way in which birds breathe, described so beautifully by

in her recent post bird lung, also means that they can sing almost constantly, rather than only when exhaling, like us.“A bird lung is nothing like a human lung. On Everest, the humans who summit without oxygen masks must move very slowly as they heave their diaphragms up and down, up and down, squeezing the air for morsels of oxygen. Meanwhile, geese fly overhead. They are not breathless with altitude. Their hearts are not hectic with slow suffocation. They fly calmly, their blood oxygenated, their wingbeats strong.

A bird’s respiratory system is a wonderfully strange thing. At the end of the windpipe is an air sac, for the storage of freshly inhaled air. The sac releases this air into thin tubes where gas exchange occurs, and on the other side of the tubes the air – now depleted of oxygen – is pushed into another holding sac. Then, finally, it is released. It’s an incredibly efficient system, allowing continuous one-way airflow of fresh air.”

But none of this explains why the wren in particular is so loud. One explanation I’ve been able to find comes from Bill Oddie (of blessed memory), who said that wrens sing so loudly because they often live in noisy environments and need to make sure that their calls can be heard above the background noise. Another suggests that their loud song might be an attempt to scare off potential predators by making them seem larger. I’m not sure how convinced I am by either of these explanations, but I’m happy for the mystery of why and how such a tiny bird can sing so loud to remain.

Now for the etymology. Troglodytes troglodytes, their Latin name, comes from a Greek word meaning a cave or hole dweller. Wrens nest and roost in small enclosed spaces: a hole in a wall, a crevice behind the bark of a tree, a nestbox, a gap amongst thick brambles. When I see them in the garden they are often emerging from - or disappearing into - the undergrowth along the bottom of the hedge. But it’s their Welsh name, dryw, that I am (predictably!) more interested in.

Dryw can roughly be translated as “tree knower”. The roots of this word have been traced back to the Proto-Indo-European language believed to have been spoken in late Neolithic and Early Bronze Ages (so somehwere between 4000 and 9000 years ago!), and the same roots can be traced in other Celtic language names for the wren: dreolin (Irish), dreathan (Scottish Gaelic) and dreean (Manx). In Welsh, dryw can also be translated as “druid”, another kind of tree-knower.

Druids were the religious leaders/legal authorities/record keepers/healers/political advisers of Iron Age Celtic societies. The first druid many of us meet is perhaps Getafix (or Panoramix in the original French version) in the Asterix and Obelix comics with his long white beard and long white robes: brewer of magic potion, harvester of mistletoe, bearer of a golden sickle. As a child, I also knew that Ynys Môn (the island of Anglesey), just off the coast of north west Wales and maybe 45 minutes drive from my home, had been a druid stronghold, from where they had held off the Roman invaders for almost a hundred years.

I’m fascinated by the ancient druids, particularly their emphasis on the oral transmission of knowledge. They left no written records and were apparently forbidden from writing their knowledge down. As a result, everything we know about them is based on Greek or Roman writers and must therefore be taken with a large grain of salt. The Romans in particular were writing as imperial invaders: their descriptions of druids are propaganda, focussed on portraying the Romans as civilised and superior and the Celtic tribes as barbaric and backward. Julius Caesar writes that the druids practiced human sacrifice, which may or may not be true - but even if it is true, is it really any more barbaric (or less civilised) than using crucifixion as a method of execution or watching gladiators fight to the death as entertainment?

Druidism was effectively wiped out by the Romans, but was revived (or reinvented) in the late 1700s. One of the key figures in its revival was Edward Williams (otherwise known by his bardic name of Iolo Morganwg, 1747-1826) who arguably almost single-handedly invented several key elements of modern Welsh culture. He founded the Gorsedd of Bards, which started life as a secret society in a similar vein to the Freemasons, with ceremonies said to be based on ancient druidic rights. He spearheaded the revival of the Eisteddfod, a competitive festival of music, poetry and other performing arts. He forged a number of medieval Welsh manuscripts to back up his claims, and also created a runic alphabet said to date back to the ancient druids. Iolo Morganwg could be described as a charlatan, or alternatively as an amazing storyteller who played a vital role in the survival of Welsh culture, language and identity at a time when Wales was seen as just another region of England1.

Tarot card of the month: The Hermit

I’ve decided to pick a tarot card again this month, rather than do a tarot reading. Like

in a recent post, I’m increasingly obsessed with spotting patterns and synchronicities, that might just be coincidences but often feel deeply significant and meaningful.This month, it’s all about the number 9 so I’m writing (again) about the Hermit, the ninth card in the major arcana. I wrote about the Hermit back in my January Compost post, because it’s the tarot card of the year for 2025 (2+0+2+5 = 9) and because I want to cultivate some of that hermit energy this year while I’m writing the first draft of my memoir (key words: solitude, searching, study, self-examination). I love this line from Beth Maiden of Little Red Tarot’s interpretation of the Hermit card:

“It takes guts to be willing to face the chaos most of us carry inside us, and attempt to sort through it and make some kind of sense of it all…”

The number 9 is commonly seen as one of completion. It’s the end of one cycle and the beginning of the next. The largest single digit number. Once you start looking, there are significant 9s to be found everywhere you look. A human pregnancy lasts around 9 months. The Norse god Odin hung on Yggdrasil, the World Tree, for 9 days and 9 nights in order to gain wisdom2. In the Bible there are 9 different types (or choirs) of angels, and 9 generations between Adam and Noah. Jesus is said to have died in the 9th hour of the day. On a personal level, the memoir I’m writing is focussed on the 9 months before my mum’s death in July 2015 and the nine months after her death, ending with my younger son’s birth in April 2016. That son is turning 9 this year. It feels to me like all those repeating 9s must carry some deeper meaning.

See for example the famous and possibly apocryphal 19th century Encyclopedia Britannica entry “for Wales, see England”.

There are also 9 worlds in the Norse universe, including Asgard, Midgard, Jotunheim and Hel.

This is such a beautiful essay Ellen (and thank you for the mention) that has so many links and connections that I need to print it out, and re-read, so this Druid in your circle is just flying by to say briefly, there is a link between Druidry and the five generations case taking…. 💕x